An Education in Unlearning — The Inheritance of Fear and the Quiet Art of Freedom

What we call “care” is often the most elegant form of control. The story of how love became instruction — and how it can become love again.education-in-unlearning-fear-control-freedom

An Education in Unlearning

What This Cycle Is About

This is not a text about childhood.

It’s about civilization.

About how obedience is woven into tenderness,

how fear disguises itself as care,

how every lesson of goodness

is a rehearsal for disappearance.“Education” here means not schooling,

but domestication —

the shaping of the self

to fit the comfort of others.To unlearn is not to rebel.

It is simply to stop continuing the pattern.

To pause before saying the same words.

To choose not to pass the inheritance of fear.That is all the freedom there is —

and all the freedom that’s needed.

I. The World Through the Eyes of a Child

The world does not begin at birth.

It begins — with a face.

The first thing the child sees is not light, but expression.

He doesn’t know words, but he knows:

if this face exists, then so does everything else.

At that moment, the mother is not a person.

She is reality itself.

She is what makes existence possible.

When she is present, the world holds together.

When she leaves, the world collapses.

She does not just feed.

She defines the structure of being:

where good means presence,

and evil means absence.

For the child, she is God in the literal sense —

omnipresent, omnipotent, unpredictable.

She commands the weather.

She decides when morning comes.

Her mood determines sunlight.

He doesn’t know that she can be tired,

or silent, or afraid.

For him, she is the law of gravity.

If she frowns, the air tightens.

If she laughs, everything becomes possible.

The father arrives later.

He is the first mythic visitor.

He comes and goes, bringing noise, movement, wind.

He is not constant — and that is the lesson.

He gives the world direction.

Through him, the child learns: there is an outside.

The father is the messenger between home and horizon.

He represents reason — cause and consequence.

The mother simply is.

The father explains why.

He doesn’t create warmth,

but he names the weather.

He gives chaos an axis.

The grandmother is the keeper of time.

She remembers what the child never saw,

and in that memory — eternity survives.

Her speech is slow,

her stories repeat,

and in that repetition

the child senses that the past is safe,

that what has happened will not vanish.

With her arrives the first form of comfort:

everything has happened before,

and everything will pass again.

The grandfather is the law of repetition.

He tells stories that do not change.

He moves the same way,

cuts the same bread,

folds the same newspaper.

He is order embodied —

the proof that stability exists.

When he speaks,

the world stops trembling.

He is reliability made flesh.

The brother is conflict.

The first rival, the first mirror.

He teaches the scale of “mine” and “not mine.”

Through him the child learns both pride and shame.

He introduces the arithmetic of love:

“if he gets, I lose.”

The sister is tenderness and threat.

She shows that softness can be power,

that being loved is not always earned.

But her presence also awakens jealousy:

why is she loved differently?

She is the first form of beauty and danger at once —

the proof that love can divide as much as it unites.

And the rest of the living world joins in:

the cat — self-possession,

the water — adaptability,

the wind — impermanence,

the shadow — the evidence of existence.

Before language, the child lives in a total field of aliveness.

Everything speaks, everything responds.

Nothing is “just a thing.”

Until someone says:

“It’s nothing.”

“It’s just the wind.”

“It’s just a toy.”

That’s when “just” enters the world.

And from that moment on,

the sacred becomes ordinary.

That’s why “Don’t trust your eyes”

is not an innocent phrase.

It doesn’t destroy naivety —

it destroys wholeness.

Before that moment,

the child lives in a cosmos.

After — in a system.

III. The Training of Helplessness

At first, it looks like care.

The blanket tucked too tightly.

The stroller strapped too firm.

The crib with no corners to reach.

Safety becomes the first law of love.

Every motion is predicted, contained,

managed by hands larger than your own.

He learns the meaning of stillness

before he learns the meaning of freedom.

When he kicks, someone adjusts the blanket.

When he reaches, someone moves the object away.

When he cries, a screen sings to him.

The lesson is clear long before language:

movement is danger.

curiosity is risk.

stillness is good.

Years later, the message will return —

in the car seat,

the classroom desk,

the office chair.

Safety belts across the years.

The world now praises what the crib began:

compliance as maturity,

comfort as virtue.

He learns to live within devices.

The screen becomes a substitute for exploration:

the forest shrunk to pixels,

the horizon replaced by scrolling.

He grows up inside a soft architecture of control —

no edges, no cracks, no wilds.

He learns to say “I’m fine here”

while the body forgets how to move toward what calls it.

Phones raise him as much as parents do.

Not through violence — through gentleness.

Through availability.

Every cry meets a glowing answer.

Every silence — a hum of digital lullaby.

He never learns to wait,

because waiting is discomfort,

and discomfort has been declared unsafe.

The screen becomes both parent and priest —

it never punishes, never withdraws.

It offers infinite reassurance,

and in that infinity —

kills longing.

By the time he walks,

the world is already padded.

Playgrounds without height.

Toys without edges.

Everything bright, rounded, rubbered,

as if the world itself apologized for being real.

And so the child grows up untouched by friction.

He doesn’t fall — and never learns balance.

He doesn’t bleed — and never learns repair.

He doesn’t chase — and never learns distance.

When we call him “dependent,” we sound surprised.

But that’s exactly what we built him to be.

We taught him to associate freedom with threat,

and safety with surrender.

We wrapped him so well

that he mistook protection for identity.

And now, when he finally feels emptiness,

he calls it calm.

IV. The Body as the First Prison

(Тело как первая тюрьма)

It starts with warmth.

Not love — temperature.

Too cold, too hot, too damp, too long.

Hands lift you, wrap you,

decide for you what comfort means.

The child doesn’t own his body yet —

he owns reactions to others’ judgments of it.

A cry means “adjust me.”

A silence means “I’ve learned the rule.”

We praise him for being calm,

for sleeping through the night,

for not needing too much.

But what we really praise

is his first surrender.

The discipline of stillness.

The small art of disappearing quietly.

Then comes the ritual of control:

feeding by the clock,

sleeping by the chart,

touch only on schedule.

He learns that pleasure must be timed,

that hunger is inconvenient,

that desire needs permission.

He learns to wait — not because he’s patient,

but because wanting is wrong.

The clothes follow.

Soft, clean, synthetic —

all edges removed, all weather erased.

He never feels his own climate.

His body no longer negotiates with the air.

It’s curated —

temperature, humidity, texture,

all preselected for comfort.

He grows up indoors,

trained to mistake regulation for peace.

He forgets what a draft feels like,

what a bruise means,

how it feels to sweat from effort instead of fear.

By the time he’s old enough to speak,

his body has already learned the hierarchy:

you may signal, but not decide.

You may ache, but not act.

You may exist — as long as it’s quiet.

Later, he’ll call this “discipline.”

Or “being easy to live with.”

But really,

it’s muscle memory of submission.

When we say “don’t cry,”

we mean: “don’t express what we can’t control.”

When we say “sit still,”

we mean: “don’t remind us that you’re alive.”

And when he obeys —

we call him “good.”

He learns early:

the body is a project,

and comfort is compliance.

He learns to monitor himself

before anyone else has to.

And so the first prison is built —

not out of walls,

but out of approval.

IV. The Body as the First Prison

It begins with warmth —

not love, but temperature.

Too cold. Too hot. Too long.

Hands lift you, wrap you,

decide for you what comfort means.

The child doesn’t own his body yet —

he owns reactions to other people’s judgments of it.

A cry means “adjust me.”

Silence means “I’ve learned the rule.”

We praise him for being calm,

for sleeping through the night,

for not needing too much.

But what we really praise

is his first surrender —

the discipline of stillness,

the small art of disappearing quietly.

Then comes the ritual of control:

feeding by the clock,

sleeping by the chart,

touch only on schedule.

He learns that pleasure must be timed,

that hunger is inconvenient,

that desire needs permission.

He learns to wait —

not because he’s patient,

but because wanting is wrong.

Mothers of Mothers

This knowledge doesn’t come from books.

It’s passed down —

mother to daughter,

generation to generation —

a science of fear disguised as care.

The first authority doesn’t arrive from heaven,

but from the doorstep —

a woman in white,

voice firm, tone absolute.

“Feed every three hours.”

“If he cries, it’s his stomach.”

“Don’t overfeed — you’ll stretch it.”

“Swaddle tight — or his legs will grow crooked.”

“Don’t pick him up too much — you’ll spoil him.”

And you listen.

You obey, not out of weakness,

but out of terror of being careless with life.

You read Dr. Spock.

The new gospel of motherhood.

He sounds modern, forgiving,

but between the lines —

the same quiet command:

control. observe. correct.

We began to understand —

but we never truly did.

We learned to describe love,

but not to trust the body.

We called it care,

but it was still containment.

And now —

my daughter does the same.

The doctor told her:

“No water for the baby. Not yet.”

So she doesn’t give it.

Generations of obedience —

hydrated by fear.

Each of us repeating the same ancient logic:

if we can prevent pain,

we can prevent death.

And so we trade freedom

for reassurance,

again and again,

until even thirst

becomes suspect.

Later, when the child can speak,

his body will already know the hierarchy:

you may signal,

but not decide.

You may ache,

but not act.

You may exist —

as long as you’re quiet.

He will call this “discipline.”

We will call it “a calm child.”

But really —

it’s a lineage of fear,

folded neatly into tenderness.

Don’t trust your eyes. Trust me.

That’s the first thing we teach them —

without even meaning to.

When they point at something living —

light, leaf, wind, bird —

we say, “No, that’s nothing, it’s just the wind.”

And they believe us.

Because they love us.

Because they still think

we can’t be wrong.

That’s how it starts:

a quiet exchange —

their vision for our comfort.

We call it “guidance.”

But it’s blindness,

wrapped in care.

Later, we will teach him to smile.

To share.

To wait.

To keep quiet.

To stay pleasant,

no matter what he feels.

We’ll call it “good manners.”

He’ll call it “life.”

And one day,

he’ll say the same words

to his own child:

“Don’t trust your eyes. Trust me.”

And I —

I will become a grandmother.

And suddenly I’ll see it all.

How every lesson of care

was also a lesson of erasure.

I’ll understand too late

that every “trust me”

was another way of saying

“don’t trust yourself.”

Now I just sit at the table.

The kettle hums.

The cat blinks.

And I try to remember

how to see again

without asking permission.

The Good Child and the Miracle

If you’re good, the miracle will come.

That’s what we tell them —

smiling, patient,

as if kindness could be traded for magic.

We say: “Be nice. Be quiet. Wait.”

And they wait —

so well

that waiting becomes their faith.

The years pass.

The fairy tale fades,

but the pattern stays:

approval as oxygen,

obedience as hope.

They learn not to want too much.

To fold their hunger into politeness.

To earn every joy.

We call it maturity.

They call it disappearing.

And when life gives nothing,

they don’t complain.

They only whisper —

maybe I wasn’t good enough.

III. The House of Secrets

Home is a secret.

That’s what we teach them next.

We close the curtains,

lower our voices,

and say, “What happens here stays here.”

They nod —

little keepers of family silence.

They learn to guard the walls,

to smile when someone asks,

to say “everything’s fine.”

They think loyalty means quiet.

They think love means hiding.

And when they grow up,

they keep doing the same —

not out of fear,

but out of habit.

They build homes inside themselves

with no windows,

no doors,

only rooms for storage.

We call them private people.

But really,

they are survivors of unspoken weather.

We think we’re protecting them.

But we’re training them for loneliness.

They grow up believing that loyalty

is higher than honesty,

that belonging

is more important than connection.

They build friendships like negotiations —

careful, half-open,

never too close to the door.

And when the world fails them,

they don’t reach out.

They go home.

To the one secret

that keeps them small

and faithful.

The Secret of Belonging

We tell them that home is sacred.

That what happens here stays here.

That the world outside can’t understand us.

They believe it.

They learn early that to belong

means to protect.

To protect means to hide.

And to hide —

means to stay loved.

We call it family.

But it’s a small country

where honesty is treason.

Years later,

we’ll ask why they don’t talk to us.

Why they don’t share,

why they turn to friends, to strangers, to screens.

We’ll say: “You can tell me anything.”

But they remember —

that once, long ago,

they did.

And the room went cold.

IV. The Gift That Erases You (Full)

“Don’t be selfish,” we say.

“Share. Give. Be kind.”

And sometimes,

they do it on their own —

out of joy, not duty.

A toy, a cookie, a bright stone from the yard —

offered with the unthinking generosity

of someone who has not yet learned fear.

We rush to praise them.

We call it goodness.

We call it heart.

And in that praise,

something shifts.

The act that was once play

becomes virtue.

Virtue becomes expectation.

Expectation becomes shape.

They start to give before they’re asked.

To smile through the ache of loss.

To offer the last piece —

just to see our faces glow.

They learn that to keep love

they must keep emptying themselves.

They learn that the safest child

is the one who never needs.

By the time they grow up,

they no longer know

where generosity ends

and self-erasure begins.

We call it kindness.

They call it disappearing beautifully.

V. The Perfectly Good Child

Be good.

That’s the rule that sounds like love.

Not brave.

Not honest.

Not real.

Just good.

It starts with tone —

the soft pride in a mother’s voice,

the relief of a father’s nod.

You can feel it —

the room relaxes when you behave.

The world becomes easier

when you don’t take up space.

So you learn to smile instead of speak,

to apologize before you’re blamed,

to soften everything you touch.

They say:

“You’re so easy to love.”

And you are —

because you’ve learned

how not to be trouble.

Years later,

you’ll still tidy yourself before entering a room,

still shrink a little when someone raises their voice,

still confuse kindness with disappearance.

You’ll be loved everywhere,

but never quite met.

We call it grace.

You call it safety.

And neither of us

dares to call it grief.

VI. The Slow One

It happens early —

a race, a game, a team.

You stumble,

a few seconds too late,

and someone laughs:

“We lost because of you.”

It’s just a moment,

but the verdict sticks.

You become the slow one.

Not clumsy — slow.

Not different — less.

No one means harm.

The teacher smiles kindly,

the team moves on,

but inside you —

a clock starts running faster,

trying to make up for those seconds.

From then on,

you hurry through everything:

answers, friendships, meals, life.

You apologize for delay

before anyone notices it.

You learn to call exhaustion “discipline.”

And when you finally stop —

years later —

and someone says,

“You can take your time,”

you don’t know what they mean.

Because somewhere,

you’re still on that field,

still hearing,

“We lost because of you.”

VI. The Lesson of the Slow

They call it fair —

same rules, same race, same clock.

But the year hides its own cruelty:

one child is almost eleven months older than another,

and in childhood, eleven months

is an entire species.

The older ones run faster,

speak louder,

fill the air first.

The younger one learns to take what’s left.

In school they call it teamwork.

In truth, it’s sorting.

Sorting by muscle, by calendar, by chance.

He hears, “We lost because of you.”

And no one corrects it.

The teacher smiles —

“Next time, try harder.”

But harder doesn’t fix biology.

What the system calls “equal opportunity”

is really a machine calibrated for birthdays.

And the youngest learn early

that fairness is just efficiency with better PR.

He spends ten years trying to catch up,

ten more proving that he’s not “the slow one.”

By then, speed is a religion,

and rest feels like sin.

VII. The Fear of Being Alone

It begins at school.

The groups, the teams, the projects.

“Find a partner.”

“Don’t sit by yourself.”

Every system loves collectives —

they’re easier to count.

The quiet ones become a problem.

“He doesn’t play well with others.”

They write it down,

as if solitude were a flaw in social software.

But some children simply breathe slower.

They need space before sound,

a pause before belonging.

No one teaches them that silence can be honest,

that alone doesn’t mean empty.

So they learn to perform connection —

to talk when they have nothing to say,

to laugh half a second late,

to share without being seen.

Years later,

they’ll call it teamwork,

networking, communication.

They’ll fill their calendars to avoid themselves.

And when finally left alone,

they’ll panic —

because the world taught them

that solitude is failure,

and presence only counts

when it’s witnessed.

VII. The Glasses

Someone gives you glasses.

Maybe a teacher, maybe chance.

Suddenly, everything comes into focus —

the grain on the desk,

the cracks in the wall,

the small cruelty in people’s laughter.

You think it’s a gift.

But sight is a social risk.

At first, they call you clever.

Then — strange.

Then — annoying.

You start noticing too much,

naming what they’d rather leave unnamed.

One day, someone laughs,

and says, “Who do you think you are?”

And something in you —

breaks the glasses yourself.

Better to blur,

better to belong.

Years later,

you’ll still squint at truth —

not because you can’t see,

but because you remember

how it felt to be hated

for pointing at what was already there.

We teach the child to compete

We teach the child to compete.

To run faster, think quicker, speak louder.

To raise a hand, to win, to stand out.

We say it’s healthy.

We call it growth.

We say, “Don’t compare yourself to others,”

after years of comparison drills.

He learns the shape of the race long before he learns rest.

The silence between bells feels dangerous —

a void that must be filled with performance.

Every success tastes like survival.

Every pause smells like guilt.

We hand him medals

and call them confidence.

We hand him deadlines

and call them purpose.

He grows up exhausted,

trained for momentum, allergic to stillness.

He tries to stop,

but stopping feels like falling behind.

And when he finally collapses,

we call it burnout.

We call it a mental health crisis.

We call it “not managing stress.”

But it’s none of that.

It’s simply the body refusing

to keep proving that it deserves to exist.

We teach the child to be honest

We teach the child to be honest.

To tell the truth.

To speak up.

To say what he sees.

At first, we clap —

so brave, so pure.

Then we flinch.

His truth gets inconvenient.

It points too close to us.

He says, “But you said to tell the truth.”

We say, “Not like that.”

He learns the subtext quickly —

truth is welcome only when it decorates.

When it doesn’t move the furniture.

When it makes everyone comfortable.

So he edits.

He sands down the edges.

He keeps the facts that don’t shake the room.

Years later,

he’ll call this diplomacy.

He’ll say he “knows how to talk to people.”

But really —

he just knows how to survive honesty.

We teach the child to be polite

We teach the child to be polite.

To say please, thank you, sorry.

To wait his turn.

To speak softly.

To not disturb.

Politeness is the first rehearsal for disappearance.

He learns how to smile when bored,

how to nod when dismissed,

how to say “it’s fine”

when it’s not.

We call it manners.

We call it grace.

But what we really mean is:

Make yourself easy to handle.

Years later,

he’ll call his numbness maturity.

He’ll say, “I just don’t like drama.”

He’ll confuse calm with dignity,

and silence with control.

He’ll be praised for being “the reasonable one.”

He’ll be trusted with everyone’s chaos

because he never adds his own.

And when finally asked what he wants,

he’ll hesitate —

not because he doesn’t know,

but because wanting

was never part of being polite.

We teach the child to obey

We teach the child to obey.

To listen, to follow, to trust the adult voice.

To stop when told to stop.

To move when told to move.

At first, it looks like safety.

We call it order.

We call it learning.

But what it really teaches

is how to wait for permission to exist.

He learns to scan faces before acting —

is this allowed, is this right,

am I good now?

He stops asking “what do I feel?”

and starts asking “what do they expect?”

Years later,

he’ll call it intuition —

that hyperalert reading of the room.

He’ll sense moods, predict reactions,

preempt conflict before it forms.

He’ll be praised for being empathetic.

He’ll be hired for being adaptable.

But inside,

he will not move

until someone says now.

We teach the child to believe in miracles

We teach the child to believe in miracles.

To wait for magic, for Santa, for signs.

To behave now — and be rewarded later.

We say, “If you’re good, he’ll come.”

We mean, “If you obey, you’ll be seen.”

He learns early that gifts are conditional,

that wonder is earned,

that kindness must be proven to the invisible.

The miracle never comes — not the way he imagines.

But the structure stays:

wait quietly, be good,

don’t ask too soon.

Years later,

he will do the same with people.

He will wait for love like for Santa —

hoping someone’s keeping score,

that goodness is being watched,

that patience will be enough.

When nothing comes,

he won’t be angry.

He’ll think he failed the test.

We teach the child to be humble

We teach the child to be humble.

To lower his eyes when praised.

To hide the spark.

To make his brightness small enough

to fit inside the comfort of others.

At first, it looks like grace.

We call it modesty.

We call it humility.

But what it really says is:

Don’t be too visible.

Don’t remind anyone

of what they gave up on.

He learns to apologize for talent,

to blur his own outline.

When someone says “Wow,”

he says “It’s nothing.”

And means it.

Later, he will call it emotional intelligence —

the art of not shining too much.

He will dim himself in every room,

just enough to stay loved.

And when he meets someone

who lives in full color,

his first impulse

will be admiration.

His second — shame.

We teach the child that we are always on his side

We tell the child:

“We’re your parents. We’ll always be with you.”

He believes us.

He believes it the way the sky believes in ground.

Then one day,

he’s called to the principal’s office.

A small mistake — a word, a scuffle, a rumor.

He looks at us, certain we’ll stand beside him.

But we don’t.

We stand beside authority.

We say, “You shouldn’t have done that.”

We say, “The principal is right.”

He learns something no child should:

that truth depends on who’s in the room.

That loyalty has a hierarchy.

That love is conditional on compliance.

He starts defending himself less.

He starts agreeing faster.

He starts to pre-empt guilt —

because being innocent

never protected him anyway.

Years later,

he’ll call it diplomacy.

He’ll say he “understands both sides.”

But really —

he just remembers the day

his side disappeared.

EXPLANATION

Why “the principal” is the turning point

Before this scene, the child lives in an internally unified world:

mother and father are justice,

the adult is truth,

authority is an extension of love.

He may be dependent, trusting, obedient —

but his dependence is not dangerous,

because it is not divided.

When the parents, for the first time, take the side of the system against him,

a split appears between personal truth and external order.

It’s not just hurt — it’s an architectural failure:

a “double hall” appears in the psyche.

Now there are:

— external truth (to survive),

— internal truth (to stay alive).

From that moment, the person begins to edit himself,

to learn to be “understandable,” “acceptable,” “not difficult.”

It is here that the adult is born —

the one who later calls lies “subtlety,”

concession “wisdom,”

and fear “politeness.”

This is the point of transition from natural trust to an institutional personality.

Before “the principal,” the child lives inside love.

After — inside observation.

The Lesson of Comparison

After the office,

comes the scale.

The world stops being round —

it gets ruled and measured.

You are not just you anymore,

you are “better than” or “worse than.”

Someone runs faster.

Someone draws cleaner lines.

Someone remembers dates.

Someone forgets names.

The teacher smiles,

divides the room by numbers.

The parents nod,

compare the papers.

No one means harm —

it’s just the system of love now.

They call it motivation.

They say, “It’s good to have someone to look up to.”

But looking up means looking down.

And so it begins —

the quiet mathematics of worth.

Every joy is half-joy,

every success a disguised relief:

for now, you are not last.

Years later,

he will still flinch at other people’s talent,

praise will sound like a threat,

and friendship will taste like tension.

He will say, “I’m not competing.”

He will be lying.

Not to others —

to the part of himself

that once wanted to exist

without a mirror.

The Family of Comparison

It starts at home.

Not with cruelty — with care.

“Look at your brother.”

“Look how your friend behaves.”

“You could learn from them.”

She doesn’t mean to wound.

She means to guide.

But every comparison cuts

a line through the heart,

splitting it into “almost” and “not yet.”

He stops asking, “Am I loved?”

and starts asking, “Am I enough?”

The brother becomes a mirror,

the friend — a scale,

the neighbor’s child — a prophecy.

Love becomes performance.

Affection — a report card.

And when praise finally comes,

it’s no longer comfort.

It’s proof that, for a moment,

you matched the image.

Years later,

he will still chase that moment —

not love itself,

just the relief

of not being the disappointment in the room.

The Inherited Voice

He grows up.

He learns tenderness, irony, restraint.

He says he’ll never speak like his parents did.

But one day,

without meaning to,

he says it:

“Look at him — see how he tries.

You could do the same.”

It slips out softly,

almost lovingly,

as if comparison were a form of care.

And it is —

the only kind he remembers.

Because this is how affection survived in his house:

by measuring, by ranking,

by turning love into improvement.

He sees it too late —

that he’s passing it on,

word by word, tone by tone,

the very language

that once made him doubt his own worth.

He doesn’t want to wound.

He wants to help.

But help still sounds like

“be better.”

The Lesson of Anger

He was told to be calm.

To breathe. To control himself.

To count to ten.

He learned.

He held it in —

the small injustices, the swallowed words,

the polite defeats.

But the body keeps its own archive.

It remembers every time he smiled instead of shouting.

Every time he agreed instead of leaving.

One day it stops cooperating.

The calm cracks.

The air becomes too thin to contain him.

He doesn’t know how to be angry.

He only knows how to explode.

Years of silence sharpen the voice into a blade.

It cuts whoever is near —

not out of hate,

but out of shock:

I still exist.

Afterward,

he feels shame,

as if aliveness were violence.

He apologizes for being louder than his pain.

He calls it losing control.

But really —

it was the first time

he spoke without permission.

The Lesson of Fear

Fear is what remains

after all lessons have been learned.

It is the echo of every “be careful”,

every “don’t.”

It sits behind the ribs,

a small, loyal animal,

trained to warn before life begins.

He calls it intuition.

He calls it awareness.

But it’s just vigilance

masquerading as wisdom.

He avoids pain,

but also joy —

because both mean exposure.

He no longer needs punishment.

He has internalized the guard.

That’s the perfect student —

one who disciplines himself

even in his dreams.

The Aftershock

When fear and anger meet,

something strange happens —

clarity.

He sees the design:

how obedience becomes shame,

how shame becomes control,

how control becomes peace.

And for a brief second,

he doesn’t want peace anymore.

He wants truth —

even if it trembles.

That’s where unlearning truly begins.

The Institutions of Care

(Институции заботы)

Fear alone is fragile.

It needs paperwork.

What begins as trembling love

soon becomes a document,

a checklist, a routine.

A mother’s hand becomes a schedule.

A father’s worry becomes a policy.

A doctor’s warning becomes a culture.

We call it progress.

We call it health.

We call it safety.

The system perfects itself:

every fear gets an app,

every question gets a manual,

every doubt gets a brand.

You can now monitor your baby’s heartbeat from your phone,

his temperature from a bracelet,

his mood from a screen.

We have built a religion of reassurance.

It has no temples, only notifications.

The creed is simple:

nothing bad should ever happen,

and if it does —

someone must be blamed.

So the mother obeys,

the doctor prescribes,

the child submits.

Love becomes administration.

Touch becomes data.

Life becomes measurable —

and therefore manageable.

The system calls it care.

But what it really means is:

never let life surprise you again.

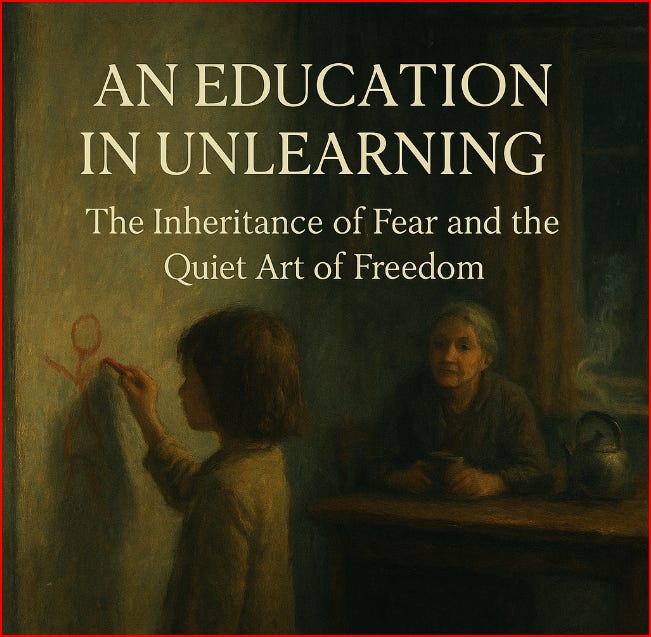

The Grandmother and the Light

The child draws on the wall.

A red pencil, a quiet house,

a line that has no plan.

Once, she would have stopped him.

Now she doesn’t.

The wall can be repainted.

The freedom — harder to restore.

She watches the line curve,

the small hand searching for form.

And something in her chest

loosens —

like a knot that forgot what it was tying.

She thinks of all the advice,

all the rules,

all the careful generations of control.

How each woman loved by limiting,

protected by managing,

feared by organizing.

How every “be good”

was really “please don’t scare me.”

The kettle hums.

The child hums back.

For the first time,

they are in the same rhythm.

She says nothing.

He draws.

The light on the wall shifts,

and for one quiet moment —

no one is teaching anyone anything.

That is what freedom looks like:

not rebellion,

but the absence of instruction.

If you read this and felt something loosen —

that was the beginning of your own unlearning.

Well written!

You're welcome! Your posts are interesting.